Looking at how the COVID-19 situation is playing out made me think about the critical decisions we had to make in 2003 – the last time we faced a similar crisis.

SARS happened 17 years ago, so you can imagine I would not remember every detail. But these were some of the guiding principles that helped us face the challenges then.

Finding clarity in chaos

Having clarity of purpose is very important in garnering support, and in getting something done.

We had to appreciate that teachers are not medical professionals. They were not doctors or nurses. We were not working in a hospital. So, we have to be clear about our role – what is it that we are doing in school during such a crisis?

Our clarity of purpose was: Since high temperature was one of the indicators of SARS, we used temperature-taking as a means to protect students.

We’re not asking teachers to diagnose SARS. We’re asking teachers – who care for their students, who know their students well, who are also able as parents to tell that a child looks unwell (red eyes, runny nose, et cetera) – to isolate children with high temperature if they happen to be in school.

To put them in an airy room with fans, windows opened. To give them a mask and ask their parents to pick them up or even send them to a clinic or hospital. In doing so, we are helping them and protecting the rest of the students.

Of course, this is different from COVID-19, where people are asymptomatic as we came to know, where they don’t have symptoms but are still infectious.

However, the point is that temperature-taking is what we could do very well, and diligently. Because of that, we could sustain it over the weeks that became months (until SARS subsided in July 2003). School staff were not confused in their mind about their role. It’s not like we were telling them to be nurses or doctors.

Equipping every child with a thermometer

When SARS hit us, we knew that it was infectious, so we closed schools. It was meant to buy us time so we could decide what to do to protect students and assemble the resources.

Right now, in Singapore, you don’t hear of students scrambling for thermometers. Ever since 2003, every child has a thermometer as part of their school equipment. Before that, nobody brought a thermometer to school. Even if you had a thermometer at home, but had two children, to whom do you give the thermometer?

We scrambled to get in excess of 500,000 thermometers – half a million – because we have roughly that population in school, teachers included. We also had to think about the kindergartens and ensuring some spares in school.

If students didn’t have thermometers, we cannot open the schools because temperature taking is our ring-fencing method – our protection method. If you’re short of 100 thermometers, or even short of one, you cannot open schools either! How can you open schools and some kids are without?

Then came another big question: Can Primary 1 and Primary 2 children take their own temperature? Medical personnel were telling us that it’s not advisable because some thermometers contained mercury. If children bit the thermometer, they would get poisoned.

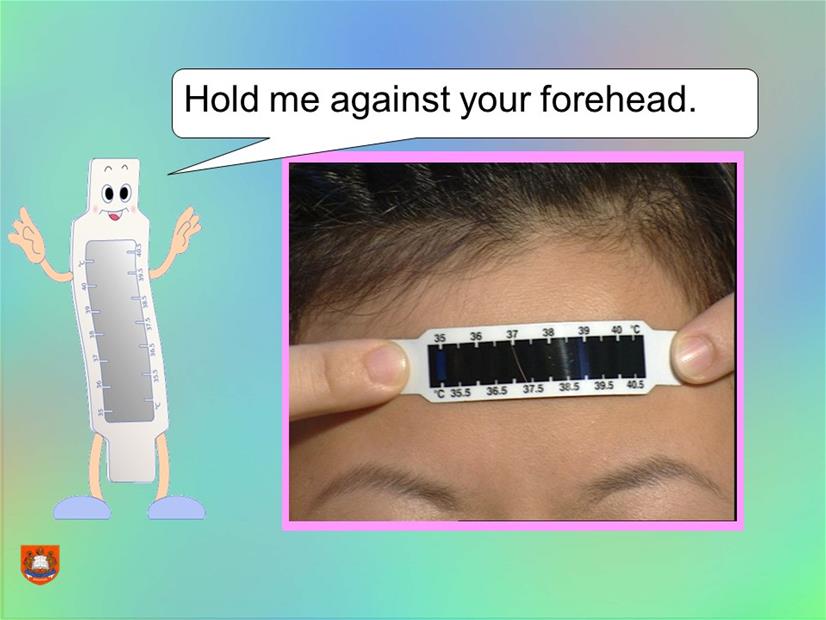

The alternative was the forehead thermometer. It’s a plastic strip that you place on your forehead, and a colour appears to show whether you have a high temperature. We sourced for these for our K1, K2, P1 and P2 children.

A slide from the SARS learning package showing students how to use the forehead thermometer. Photo credit: Curriculum Planning and Development Division, MOE.

We found the man who imported forehead thermometers into Singapore. He was a good man, but said, “No way, there’s no such stock.” We were looking to buy 200,000 strips. I offered to speak to the supplier from America.

The CEO of the company got back. He was sympathetic and very happy to help! However, he said, “We have the strips but we have not packed it. They are not even cut and are still in sheets.”

I said, “Not a problem. If I buy 200,000, can you imagine the amount of packaging I’ve got to throw away? Please sell them to me as it is, and we will cut them out ourselves!”

Upon looking back, I wish we had taken photographs. We were not in the habit of taking pictures then. But you can imagine, each sheet had around 240 thermometer strips, and boxes of these big sheets arrived outside my office. We worked with the schools to cut out the strips and put them in little zip-lock bags that schools bought ourselves.

Still, the forehead thermometers were only accurate to plus-minus one. In the end, we decided to coach the P1s and P2s to use the standard thermometers.

It became such a discovery that the children could do it! They were the most conscientious when taking temperature.

If you were watching TV during that time, news broadcasts from schools always showed a P1 or P2 class taking temperature. It was such a novelty. Everyone was so heartened that these children could monitor their temperature.

Today, we take temperature-taking by children for granted. You see children put a thermometer in their mouth and write down their temperature. We don’t even think twice about it. But in those days, we had to start from scratch.

Staying committed to our purpose

We also had to stand firm, quite literally.

What happens if the same child keeps getting sent home because he has a high temperature? The parent might say, “Before I sent him out, as per your instruction, I took his temperature first. He was okay! He walked to school, and he got a high temperature. Just keep him there. He’s fine. Nobody has SARS in my family.”

We had lots of conversations like that. What do we do? Should we make an exception in such a situation?

We cannot. We are not doctors or nurses. If we do this for one case, there will be a second case, and a third. After a while, you’ve got no clarity of purpose. Unfortunately, we have to isolate this child to protect the rest of the school.

Now, what if the father says, “Okay, I’ll bring him to see a doctor, and the doctor will certify he has not got SARS. His temperature is always quite high because he is a unique boy.”

Can you accept that letter? If you do, how many parents are going to run around asking doctors to certify? Should we do this? We are in a crisis!

We had to stand firm and do our part vigilantly without any lapses. Some schools got scolded by parents, because some parents are frustrated. They don’t mean to be nasty. They are so frustrated because their child is always having a high temperature. But we explain, and we say please understand because there is just no other way we can let the child in. Because if we do that, the line is crossed, and later on we will just fray. The whole system will just break down.

We were always on our toes. We didn’t know what will crop up when. We never knew when we may need to shut schools.

Educating a nation

During SARS, we realised we needed to help our students learn more about the virus. This would help them know why they had to follow the precautionary measures, and perhaps they would share this information with their families too.

The Curriculum side of MOE was very busy churning out educational material to do with hygiene, and sending them to schools.

There were very basic things like, What is SARS? How do we keep ourselves safe? What do we do to help each other, and to protect each other?

These were written simply for younger children, who will be the ones to really need the information. When the young children bring these things home, the parents will tend to also look at it. We were not telling the children to go hand this to your parents. If we wanted to reach out to the parents, we used national broadcast, and there were lots of national broadcasts during that time.

After SARS, we decided that we should keep the process of temperature taking in school. We made sure that all children have thermometers. At the beginning of the year, they check if their thermometers are in good condition, and we have a refresher exercise to make sure that everybody knows how to take their own temperature.

Recently, I spoke to a P1 child, and saw that she was recording her temperature in her school diary. At the top corner there’s a box to record the child’s temperature.

I asked, Is it difficult? “No.” Any accidents? “No, it’s part of our routine.”

That’s why when COVID hit, we didn’t need to immediately close schools. We could activate precautionary measures fast. We didn’t scramble for thermometers because we’ve always kept a supply. Unlike those early days, when we counted thermometers one by one.

One of the fearsome things about a crisis is taking things for granted, and having higher and higher expectations, but not realising how these things come about.

Taking things for granted doesn’t prepare us for the next crisis. We’ll be so helpless. The next crisis will be different, as COVID-19 is proving to be but certain core elements of how we handled SARS will help to see us through.

Singapore has got core elements that will hold us together. People know how to come together, make sacrifices and work as one. We should be grateful for that.

Ms Seah Jiak Choo served as the MOE Director of Schools in 2003, and later Director-General of Education before officially retiring in 2009. She continues to contribute to MOE in the capacity of an advisor, on the professional and leadership development of the teaching profession as well as other education matters.

.jpg)