Bringing Humanities to Life and Making it Sing

04 Sep 2020

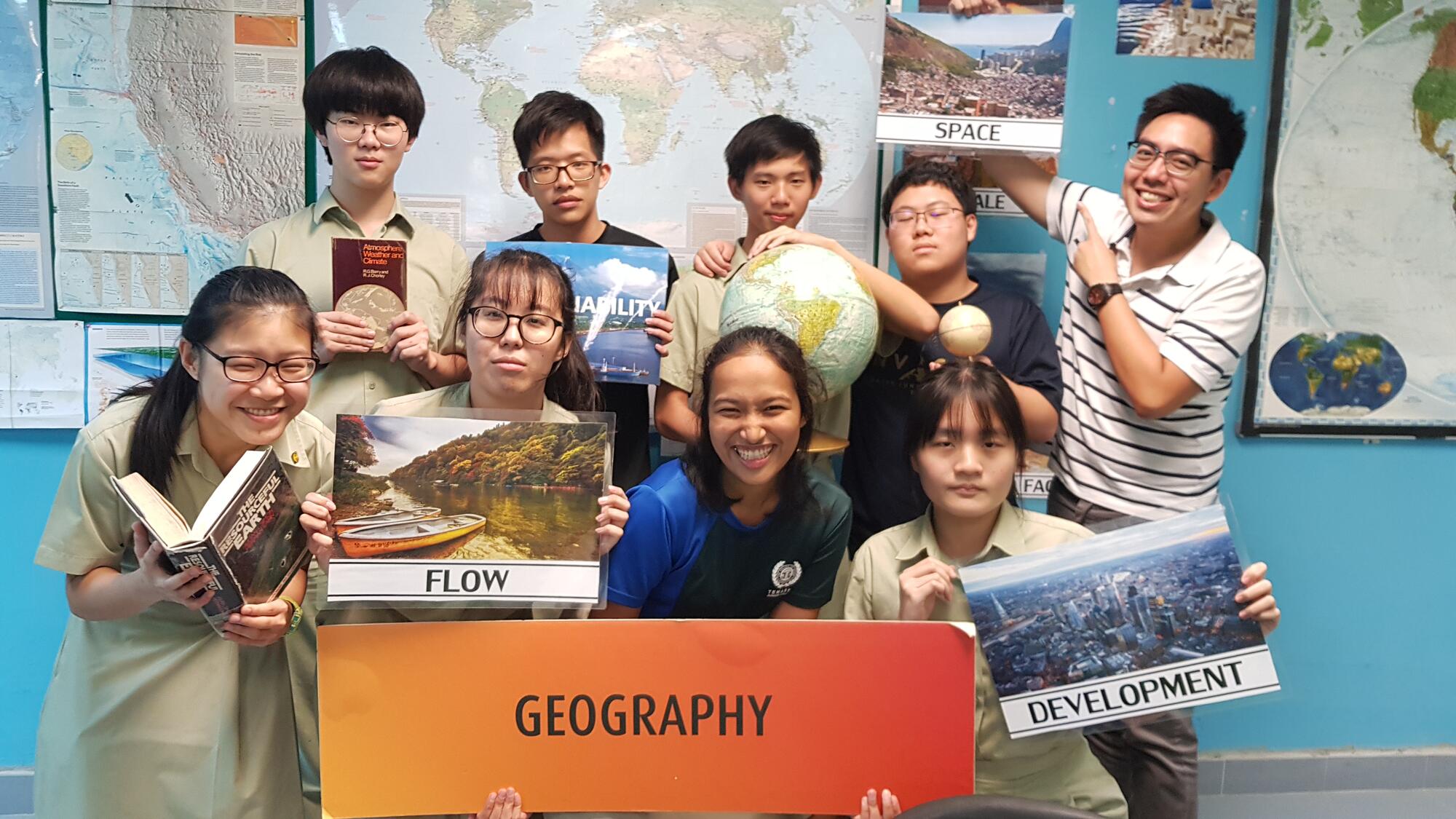

Mr Jared Wong connects students’ learning with life lessons, whether it’s during Geography class, Choir practice, or inter-disciplinary programmes.

Wong Wei Ming Jared, Temasek Junior College, Outstanding Youth in Education Award 2020 finalist

The World is the Best Classroom

Before graduation, my parting words to my Geography students have been to never lose their “worldly wonder”. My own sense of “worldly wonder” was ignited during a school trip to the North Island of New Zealand while in Secondary 2. It opened my eyes to the beauty of the world and what it has to offer. I can vividly recall the kaleidoscopic explosion of the geothermal pools at Wai-O-Tapu, breathing the pungent smell of sulphur in the air in Rotorua, and admiring the breath-taking view of Auckland’s urban built form from the Sky Tower. The trip was momentous for me as it connected the geographical content learnt in the classroom to the real-world context.

That experience convinced me that the world out there is the best classroom and I try to help my students experience that as well.

One of the ways I do this is through local and overseas field investigations that provide hands-on learning opportunities for students. My team has designed packages that have enabled students to probe various issues — from questioning what makes Changi Business Park attractive to transnational corporations to assessing the sustainability of limestone and mining landscapes in Peninsular Malaysia.

Fieldwork sets students off on adventures that allow them to explore their surroundings, record their observations and carry out their planned research. For instance, when looking into the liveability of Bedok, they first have to understand what factors contribute to the ‘liveability’ of a place. When studying sustainability, students visited Kuala Lumpur and Kuantan to analyse the connections between the economy, nature and the urban built environment.

I want my students to know that the lessons of Geography are part of their everyday life, so I use curriculum artefacts such as Barbie dolls, Starbucks coffee and aeroplane models to teach them about supply chains and the nature of the global economy.

Students are intrigued to find out where these objects and their sub-components, that are part of their lives, are sourced, assembled and then sold to reach our homes.

When COVID-19 threw a spanner in our plans to visit field sites, my team and I decided to get adventurous. We put together Virtual Reality (VR) videos of places my students would usually visit to conduct fieldwork. For instance, Eunos Industrial Park. Thanks to these videos and information packs put together by my team of teachers, students could still ‘gather’ data on noise pollution and air pollution to understand the impact of industry on the surrounding environment. Not only did my students enjoy their virtual trips, these videos expanded my teaching toolkit.

Every Lesson as a Performance

Apart from my love of Geography, I also have a love for music. I am a chorister, and I see a connection between what I do as part of a choir to what I do in the classroom.

Just as you want every song that you sing to leave a mark on your audience, so too, as a teacher — you want every lesson to be a ‘performance’ that touches students at a deeper level and draws them in to the subject.

I saw this in action with my JC Geography teacher, Mr Charles Elwin. He was a great showman whose every lesson left a lasting impression.

Music features prominently in my teaching. My lessons often begin with a music video that foregrounds the topic of discussion for the day, from Alicia Keys’ Empire State of Mind to illustrate New York as a 24-hour city, to Queen’s 1985 Live Aid performance in questioning the role of international aid in enabling global development. These videos inspire students’ “worldly wonder” as they discover interesting geographical phenomena embedded in popular culture.

Another thing I learnt from Mr Elwin is to spar intellectually with students by asking good and analytical questions to build inquisitiveness. But the questions you ask have to be differentiated to the profile of the student. This is much like matching choristers to the right section of the choir.

So, I experimented with different teaching mediums for different learning profiles. For instance, letting visual learners explore how to represent Global Production Networks through maps or engaging kinaesthetic learners by organising an event such as the #tjczerowastesunday movement for them to reflect on their waste patterns and take action to reduce it. Different lessons become opportunities for every student to find his or her place and learning rhythm, just like the crescendo of different sections in the choir at different parts of a music score.

Adding a Human Touch to the World

Three years ago, I initiated SING! — a choir meet that extended across a few schools. It was a day of workshops and group singing culminating in a concert. The purpose was to encourage the love of singing and to grow a sense of community and teamwork. When my students sang together, they felt connected, engaged, part of something bigger than themselves. This is what I want for all my students.

Song also has the power to bring humanity to our work as teachers. During the COVID-19 outbreak, a few teachers and I came together to film a music video and sing an adapted version of ‘Stop’ by the Spice Girls. On the one hand, we wanted to capture the funny moments that our students experienced during this Home-Based Learning period. On the other hand, we hope that it would encourage our students during these challenging times while remaining hopeful for our return to college after the circuit breaker.

I am most heartened to see this sense of wonderment and connectedness when my students, both past and present, send me postcards, photos and videos, excitedly sharing with me a geographical phenomenon that they learnt about in class and which they have now seen. Sometime back, one of my students sent me a photo of herself ‘kissing’ a cobblestone path in London. Thanks to the photo, we discussed fervently about the ways that a city’s built form comes to be. Her exuberance in experiencing it for herself expressed itself in the photo. It was an exciting moment for me — “worldly wonder” had taken root.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)