For the last four or five years, I’ve been creating “walkthrough videos” on YouTube.

For those unfamiliar with the term, “walkthrough videos” are step-by-step guides for popular games produced by expert gamers to help others get through different levels in a game.

My videos, instead of taking my viewers through games, take my students through various concepts of Geography. For instance, I’ve done videos for topics like Living with Tectonic Hazards, and Impact of Water Shortage.

Taking the cue from the students

The idea of walk-through videos actually came from my students when they asked me to make one for a particularly challenging topic. I had no idea what they were but once I got it, I saw how it would be useful in letting my students watch as I draw and annotate diagrams or I narrate an explanation with key ideas popping up on screen.

Over time, with my students’ feedback, my videos became shorter. I’d break topics into five to 10-minute chunks, which students could understand easily.

They could learn at their own pace, review just the videos relevant to their doubts, and they could do this at their own time. They were in control of their own learning.

How Flipped Learning helps classes

This was how I became very used to the idea of learning on the go, even before Full Home-Based Learning kicked in this year. Before COVID-19 hit, I was already experimenting with flipped learning. This is where we front-load the teaching of content, either through videos or by getting the students to read certain parts of the textbook before they come to class and engage in discussions to clarify their doubts.

In class, we will have a pop quiz to see where their baseline of understanding is. Has everyone done what is required? Who are the ones who are confused? What are the key things I may need to cover again? I use five minutes to find my baseline. The next ten minutes, I cover what is missing, then we have another conversation – a deep analysis of certain concepts that I believe they should know; certain types of questions that I think are important.

When I do flipped learning, the biggest advantage to me is I have time saving. I have found that the pace of the lesson is easily 30% to 40% faster than traditional classroom teaching. This is because my students come to class with some knowledge and understanding of the topic. The time spent in the class is used to clarify doubts and reinforce ideas – this way the learning is also deeper.

The time freed up leads to rich discussions in class, hence a better understanding of the topic. Students like hearing from each other and they remember what their peers said. They have time to give their friends a hint and nudge them along. There’s time for me to push the kid who needs that extra support.

So the biggest benefit of flipped learning: the time in class is used to do better the things that can only be done face-to-face.

Adapting and exploring during HBL

Flipped learning does not mean that the pre-learning has to take place online. During the time when students were alternating between a week of school followed by a week of HBL, I set a lesson for my Sec 1 students on the topic of tropical rainforests, which required them to take a walk.

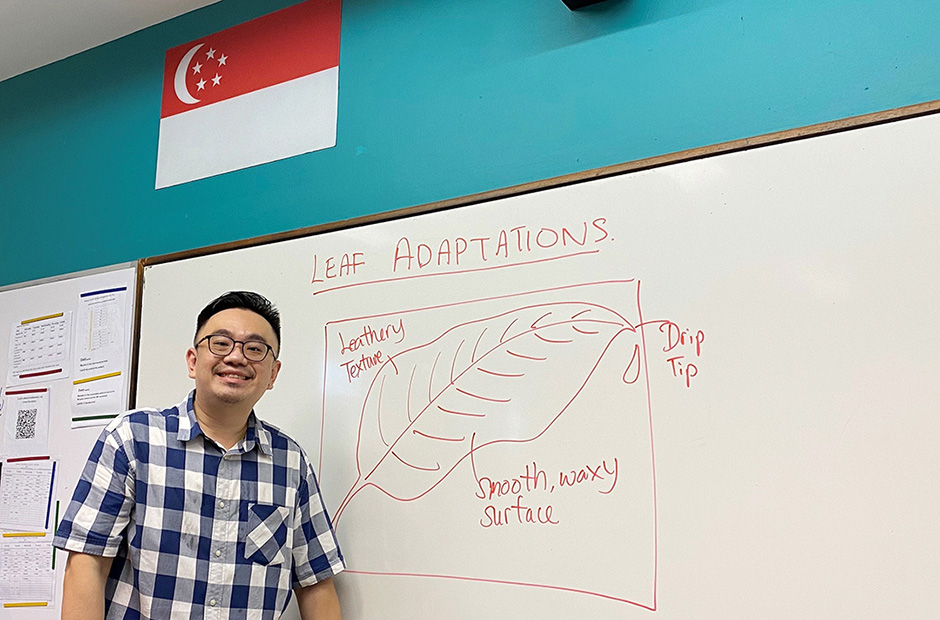

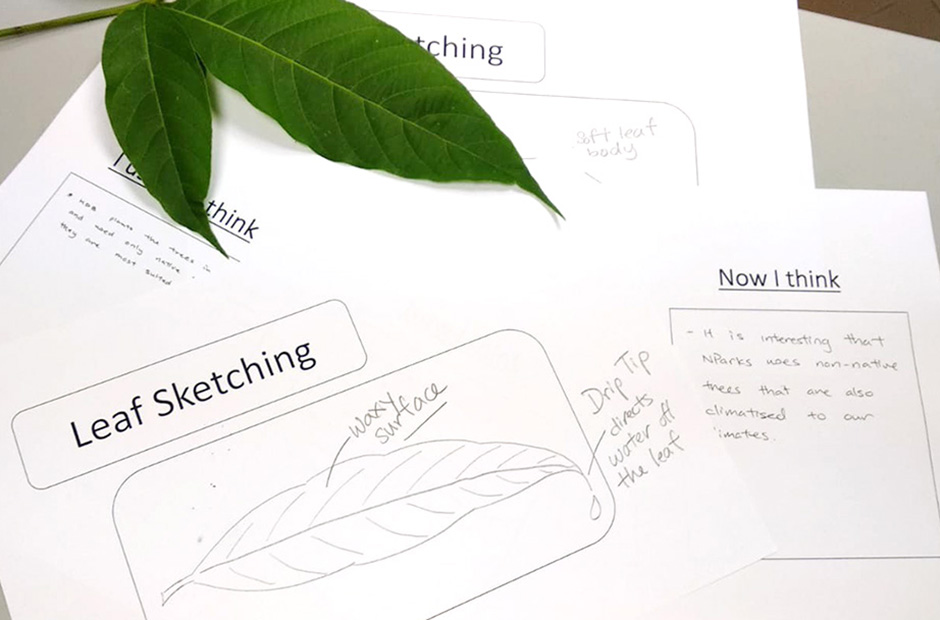

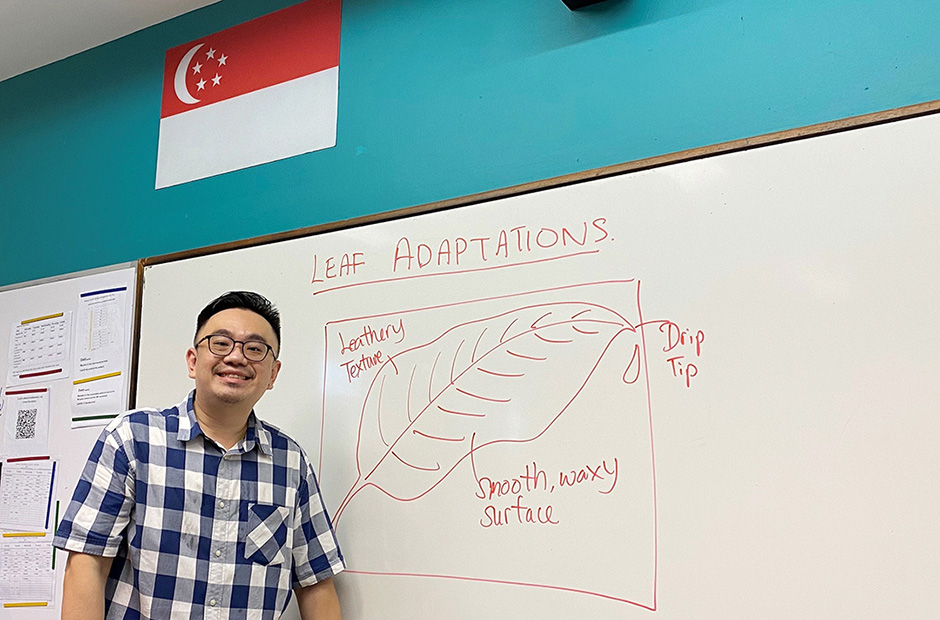

Their homework was to find a tropical rainforest leaf in their neighbourhood. From their lesson in class, they already knew the characteristics of such a leaf – leathery skin, drip tips, channels along the veins. So now they had to find one and do a sketch.

Once back in school, as a group, they looked at the leaves to see which ones were typical of tropical rainforests and which weren’t. Amazingly they saw that although they lived in different estates, many of them had come back with leaves from the Cinnamomum Subavenium tree.

That triggered the question: Why was this so? Tropical rainforests were supposed to be diverse, so why the homogeneity?

It triggered an intense discussion peppered with many questions and suppositions until they landed on a surprising realisation: A large proportion of Singapore’s trees are planted by the National Parks Board (NParks). And depending on the year, NParks plants the same species of tree across the island.

That was an “Ah-ha” moment for them that got them thinking beyond their immediate lesson to the environment of their city and what goes into developing it. It was a reminder that this wasn’t just an academic lesson about leaves.

To me, it was also a reminder that knowledge can be found anywhere – in books, in a video in our mobiles, in our surroundings. The classroom is a meeting place for our discoveries.

10db6ca7a8a66eb2afccc900c73e6f2e.jpg)