From “I’m okay” to “It’s okay”

15 Oct 2020

“I’m okay,” says your child when you ask him how he is. But is he really okay? Ms Joanna Tan, a Guidance Branch senior specialist in the areas of mental health and resilience, shares insights into how children may be really feeling when they say, “I’m okay.”

“How are you?”

Do you find yourself habitually responding with “I’m okay”, yet feel a tinge of discomfort at how untrue that really is? “Just super busy,” you may add to sound more authentic.

Sometimes, saying “I’m okay” comes from a need to keep things cordial in situations that do not afford us a chance to bare our souls. Other times, it could be a convenient response to appear put-together regardless of how we may actually feel.

If, as adults, we experience this, our children could very well be saying “I’m okay” when they do not mean it. If yes, we need to ask ourselves, why they may feel compelled to show that all is well.

The need to be perfect

A global survey among parents conducted by Varkey Foundation in 2018 found that a top concern among Singaporean parents was the cost of living, and whether their child could secure a job and a successful career.

This could lead to pressure on children to do well, influence their perception of what “successful” means, and prompt them to set high expectations of themselves.

Even though our education system has taken steps to dial back on the over-emphasis on grades, some parents and students may still be stressed by the pressure to meet academic and other performance expectations. Others may struggle with social expectations of being accepted in a desired peer group.

Outside of school, children now also need to deal with society’s increasing emphasis on social comparisons. Our youngsters are digital natives, and many may try to impress others with picture-perfect social media posts, vying with one another for the most views and likes.

However, when does striving for excellence become a more sinister issue of unhealthy perfectionism, and a fear of looking weak and vulnerable in front of others? A key ingredient is the harsh inner voice when unrealistic standards are unmet. This self-critical voice equates mistakes, failures, and sometimes the lack of accolades, to shame and unworthiness, driving home a persistent sense of feeling not good enough.

Other than the pressure that children put on themselves, parents may also unintentionally place pressure on their children through well-meaning attempts to help.

In a five-year study led by Associate Professor Dr Ryan Hong of the National University of Singapore, the research team found that the more parents interfered in their child’s problem-solving attempts, the more likely the children were to be afraid of making mistakes. This maladaptive perfectionism means that children get excessively concerned over their mistakes, and assume that others have high expectations of them, which they will be unable to meet.

So instead of helping your child solve the problem, give them time to figure it out on their own first.

And if your child has made a mistake, parents should assure them of their strengths or what they have done well, before addressing their mistakes. This will teach children not to be scared of making mistakes, to learn from mistakes and also be more open to asking for help when needed.

They may hide their pain

Sometimes, saying “I’m okay” is just a way for children to avoid facing difficult thoughts and emotions. In the midst of COVID-19, most families would have experienced the ripple effect of economic and social stressors to varying degrees. Many youths are grappling with catching up with school work, preparing for examinations, and for older youths, worries about further studies and job prospects.

Some may rationalise their struggles by thinking: “I should just try harder to deal with it.” Others may fall back on their preference for self-reliance with: “I should not depend on others to solve my problems.”

However, these two “should” mindsets contribute to the mental barriers your children may have when it comes to seeking help. They may not recognise the need for help, and may not perceive that the problem is serious enough to require help. How would children know if their stress and emotional pain is something serious that warrants more than trying to cope on their own?

A first step is to encourage them to be vulnerable and share their thoughts, so parents can look beyond the surface to understand what your children are really thinking and feeling.

It’s okay to seek help

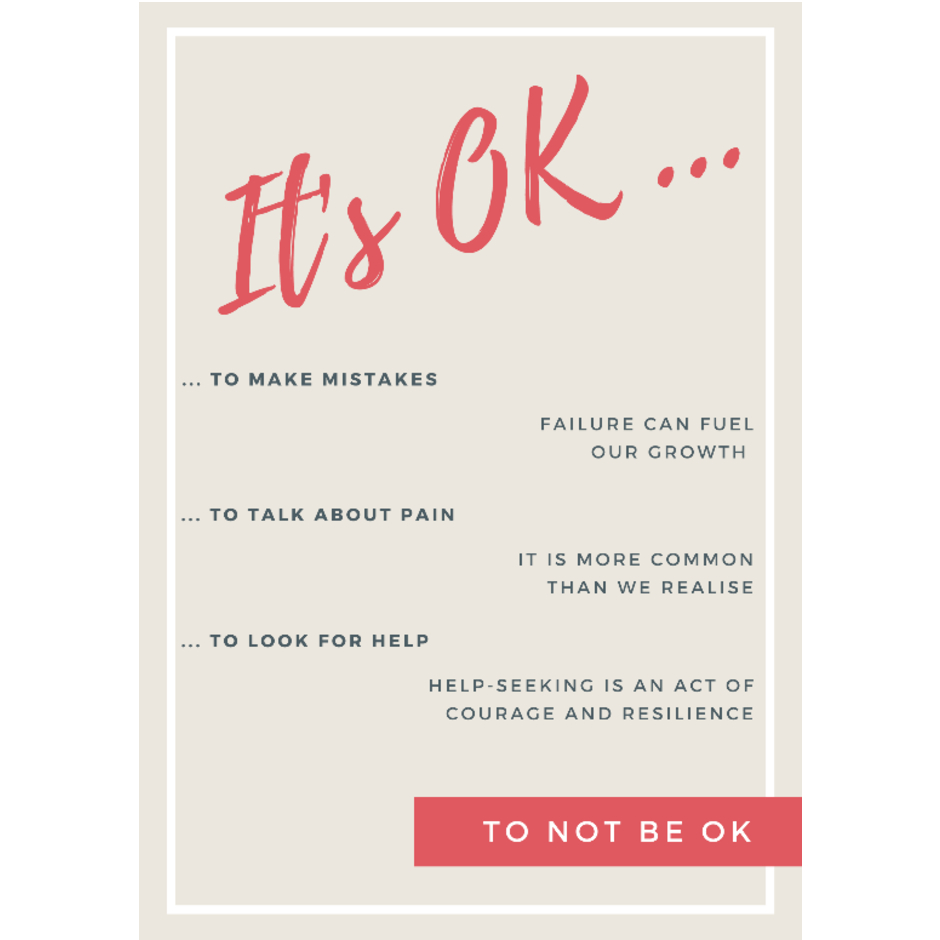

With a slight shift in mindset, you can help your children move from saying “I’m okay” to thinking “It’s okay”.

Their self-critical voice will need to be re-trained to sing a different tune that it’s okay to make mistakes or that a mistake is not the end of the story. Help them realise that failure is a necessary part of life’s growth journey and practise some self-compassion.

Guide them to temper their expectations and be kind to themselves when they meet problems along the way. This will help them to cope more effectively and bounce back when they encounter difficulties.

Your children’s self-reliant voice will need to be taught to see that everyone has limitations and it’s okay to find social support to share their struggles. It’s okay for them to turn to their peers, teachers or school counsellors for help and support. Together with others, you and your children will be in a better place to discern if further professional help is required or whether they can learn some new ways of managing their emotions and problems.

In fact, it’s okay to not be okay. As you take care of your children’s mental well-being and strengthen their resilience through the current challenges, they will be better prepared for the future.

.jpg)

.jpg)