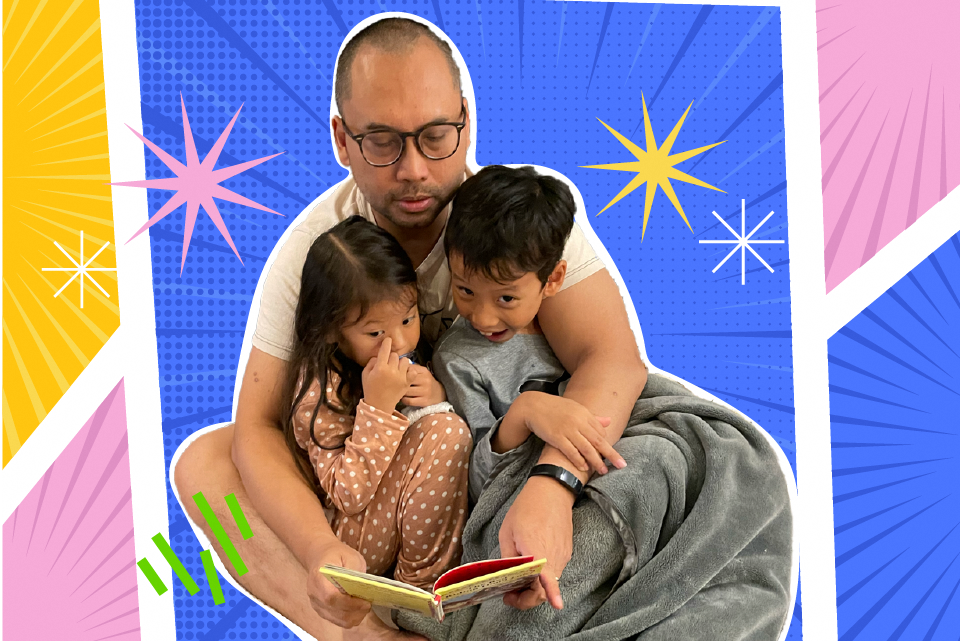

‘How we eased the stress of school for our special needs child’: Three parents share tips on what works

17 Aug 2023

.jpg)

When stress at school extends beyond a few weeks, it can become chronic and need more attention from parents, says psychologist Samantha Tang who is also a mother to two children with special needs. Hear from her and two other parents of children with special needs on some strategies to dial up the support.

Dealing with highs and lows is a natural part of life at school, but how can you tell when your child with special needs is stressed at school? Can you tell what the cause is, and how can you address it?

It usually starts with a change in behaviour, says Ms Samantha Tang, a psychologist in private practice and lecturer at the National Institute of Early Childhood Development. She has two children with special needs, one of whom is in mainstream school.

When older son Samuel, 14, was in primary school, he might come home and have meltdowns, crying and shouting from feeling overly anxious about keeping up with the rhythms of school, along with the cycles of homework.

Samuel has learning and attention difficulties, among other medical concerns.

As he spends more time than his peers to grasp and retain the same amount of information, that means less down time and more impact on his stress and anxiety levels. Ms Tang’s younger son Joshua, 11, has a rare, degenerative medical condition, is bedbound and does not attend school.

In her 22 years of working with children with special needs, and the many years of caring for her own, she observes that when the children are stressed, telltale signs could come in the form of disruptive or aggressive behaviour, task avoidance, and psycho-somatic symptoms such as headaches and stomachaches. Those attending school may try to skip classes. Internalised behaviour is seen as anxiety, depression and a low mood in general. Some other indicators of stress include changes in eating or sleeping patterns or when the child is teary, tears up paper, rushes through their tasks, or throws tantrums more frequently.

These changes do not blow over quickly but are sustained over a period of weeks. The causes can be difficult to identify, as at times, the symptoms show up weeks after the trigger. This makes treatment difficult too.

“For some children with social anxiety or with autism, social communication and interaction can be stressful. Whereas for a child with dyslexia, reading and writing are stressful. For a child with dyspraxia, where motor coordination is not as developed, PE time is stressful,” she elaborates.

To help your child cope with school stress, Ms Tang and two other parents of children with special needs have the following tips to share (some of the tips may more be relevant to students in mainstream schools):

1. Give extra support and care

When you notice signs of stress, do step back and reduce expectations and demands of the child, advises Ms Tang. Seek to understand your child’s needs, and be present when sitting with them, actively listening without being too quick to give comments.

In talking, you may also try to find out if something is happening in school, for example, if they are being bullied or teased.

Mrs Eleanor Goh, mother to a 16-year-old boy with dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), finds that lending a listening ear has been helpful when he feels overwhelmed by too many competing demands or deadlines.

“We encourage our son to talk about his feelings and emotions. We spend some time at the end of each school day to check in with him and address any social or emotional issues he may be having. Such times strengthen our parent-child relationship, and allow him to practise managing social and emotional issues and problem-solving skills.”

Ms Tang finds it useful to share advice with her son through telling stories of how others have overcome similar situations, and drawing scenarios out on paper, so her son can visualise the problems.

2. Communicate often with your child’s teachers

“Keep the communication lines open with school teachers,” says Ms Tang. “Take the initiative to reach out to the teachers and be open to their feedback.”

For students with special needs in mainstream schools, it helps to be open with the school on the nature of the child’s needs during school enrolment, says Ms Tang. With increased awareness, the school may be able to allocate the child to a class with a more experienced teacher and/or with fewer students with needs.

She also suggests collaborating with the teacher to ensure that the volume and difficulty of the homework is pitched at the child’s level.

Teachers can also give better feedback when observing the student with the right lens. Ms Wong Wei Yuan, who has a nine-year-old boy with autism, shared how her son’s teachers noticed that he was struggling with understanding social boundaries.

“Initially, I received many calls from school and I was quite affected by it. Later, I got used to it and would take what the teacher said objectively, and think of ways that I can help my son to improve.”

She embarked on working with him on his understanding of social norms; she used stickman drawings with speech and thought bubbles to help him understand both his own perspective and how his actions affect others.

“I’m very thankful for the teachers’ feedback. That feedback helps me understand whether the strategies that we are working on are effective or need to be modified. We have also tried to reinforce the strategies that the schools use that have worked.

“For example, the school uses a visual countdown timer to help him keep track of time. We now use a similar timer at home to help him understand that his assignment needs to be completed within a certain time.”

3. Be positive and break tasks down for your child

Ms Wong finds that exhibiting a positive attitude coupled with breaking down a task into bite-sized pieces help with her son.

“Instead of constantly saying ‘No’ and pointing out areas to improve, I learned to be very positive when I’m with my son. I give positive encouragement when I’m coaching him, and highlight to him areas where he has improved. We also acknowledge all his efforts, such as when he writes more neatly, or uses a greater variety of words in his compositions.”

Ms Wong’s son struggles with writing compositions and comprehension worksheets. To help him, Ms Wong breaks down the writing task to complete over several days, completing one paragraph a day. She has also sent him for educational therapy where he is taught how to break down the tasks into smaller, achievable steps.

4. Aim for a good school fit

Find a school that best suits your child’s approach to learning, strengths, needs and interests – be it a special school or mainstream school.

“Prioritise your child’s needs, and understand his or her strengths, then showcase and support your child’s strengths and interests,” advises Ms Tang. “A good fit is important. Be open to different school options. Some parents feel it is a ‘waste’ not to enrol their child in their alma mater, but your child may need an environment with smaller class sizes, less emphasis on academic results, more support, and a school where they offer the sports, music or arts CCA that your child is interested in.”

5. Redefine success by focusing on their strengths

As stress can leave children feeling anxious and vulnerable, try to find their strengths and give them opportunities to use them in their daily life. This can spark joy and lift their esteem, says Ms Tang.

She also manages her own expectations of her son’s academic performance, choosing to look at school as where Samuel picks up important life skills such as teamwork, planning and organising, and communication. It helps to “see the child for who he is and not what I want him to be”, she offers.

Mrs Goh places mental well-being as a priority and tries to infuse stress-defusing activities into her son’s schedule, such as sports and exercise. Every day after school, she sets aside time for him to do anything but hit the books, so he can rest and recharge

“We aim to have a holistic lifestyle, and nurture my son’s love for drawing, playing the drums, ukulele and bagpipes. These diverse experiences give him a broader perspective on life and help him relax. This way, relaxation becomes ‘natural’, something he turns to because he enjoys it.’”

6. Don’t feel shy to reach out for help

Putting different forms of support in place can help grow and develop your child with special needs. Such support can help them learn better, and give them confidence and boost their self-esteem to know that many people care about them.

Ms Tang gets her parents involved in fetching the grandchildren to appointments, and friends may help with the grocery runs. She also gets insights from families who are facing similar challenges, and “unloads” with trusted friends. This extends benefits to her as a caregiver too; “just knowing I can reach out and talk to someone helps”.

“Like a chair with legs, I strongly believe that we have to build ‘legs of support’ for the special needs child, and some need more legs than others,” says Ms Tang. “This support can be from the school, help from outside the school, and of course, the parents themselves.”

For more stories on support for children with special needs:

We are on Telegram! Subscribe to our channel: https://t.me/schoolbag_edu_sg