How should we see ‘play’?

The word ‘play’ often carries negative connotations among adults, being viewed as the opposite of work and study. “We often hear ‘please don’t play, go and study’, or if you’re working, then you’re not playing,” Mr Lee observes. But he thinks we got it backwards. “From our personal experiences, most of us have very positive memories of play. We remember the fun moments rather than the times we were working intensely. Play is positive.”

This perception of play as the antithesis of productivity, Mr Lee suggests, misses its true value. Play offers significant developmental benefits, particularly in building a child’s sense of agency.

“One thing that I really like about play is that most of the time, the player is in control. We are in self-directed mode,” he says. This element of control and self-direction in play, Mr Lee explains, is vital for children’s development. It helps them build confidence in making decisions and managing their own learning – skills that become even more crucial as they progress through primary school and encounter more structured expectations.

Making time for unstructured play

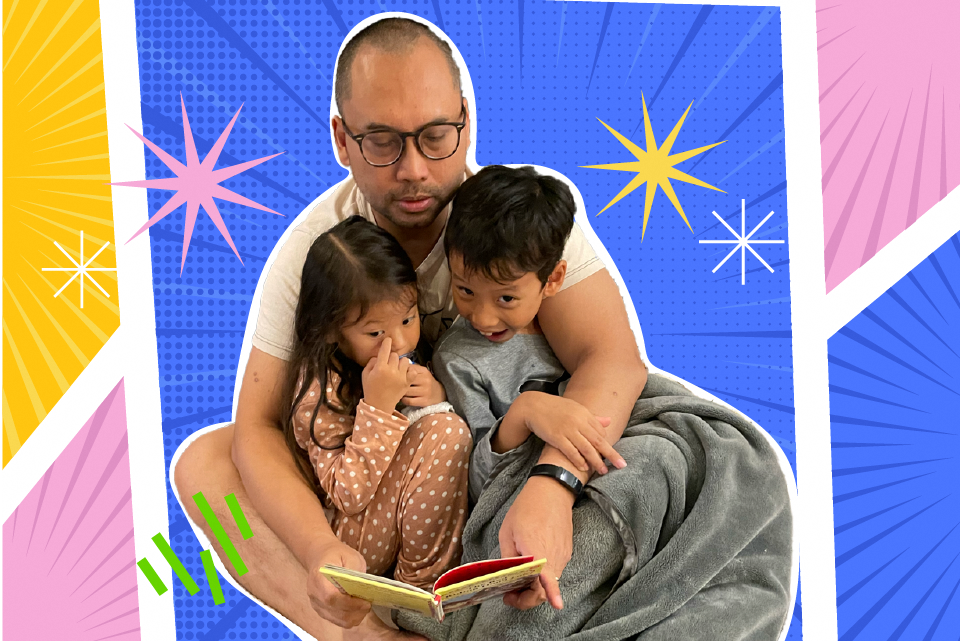

As a parent himself, with two children in primary school, Mr Lee says that he can “totally identify with the peer pressure that Singaporean parents are facing” when he hears about friends sending their children to extra classes.

“One of the few things that (my wife and I) very intentionally do is to set aside time for play,” Mr Lee shares. He admits that it can be challenging now that his children are in middle and upper primary, and their time is increasingly taken by up homework and after-school programmes.

This is where the intentionality is particularly key. “We make sure that there are a few times in the week where we bring them to play sports, go to the playground, go to the park, or just let them choose something that they want to do,” Mr Lee says.

He adds that he consciously supports what his children want to do. “As parents, we shouldn’t just cut off their opinions and decide on things for them. Where we can, on a day-to-day basis, give them the agency to choose. If they learn to make choices from young, when they get older, they will know how to make choices for themselves as well.”

Short-term measurements vs long-term growth

This nature of exploring with open-ended, inquiry-based play is “what we need for our whole life”, Mr Lee says. “It’s not only primary school. Please don’t let this sense of curiosity, playfulness, openness be lost.”

Of course, reality has a way of creeping in. A less-than-stellar test result, a comparison with a friend’s child – and suddenly the instinct to double down on academics kicks in. “Let’s say, you see test scores and realise, oh, my child is not doing ‘well’. Parents tend to have a knee-jerk reaction when we see this,” he acknowledges.

But he encourages parents to stay focused on their long-term aspirations for their children. “We should all remember what is important for each of us when we want to look at our child’s long-term growth. Is it compassion that we care about? Is it good character?”

Ultimately, when it comes to supporting your child through a big transition like entering primary school, Mr Lee offers a surprisingly simple answer: Love your children. “Children feeling the love of their parents gives them lots of strength to take on many challenges they have in their life.” And letting them play – and playing with them – is a big part of it.

This story is adapted from a podcast by the National Institute of Early Childhood Development (NIEC), where Dr Siti Shaireen Selamat, Dean of Faculty and Leadership Development at NIEC, chats with different experts about preparing children for their primary school journey.