There is stress, and then there is STRESS. What’s the difference, and does that mean that as a parent, you must remove all stress from your child? “We can’t develop resilience by avoiding stress. We don’t develop resilience by avoiding life,” says Prof Stanley Kutcher, expert in youth mental health.

As parents, our job isn’t to wall off our kids from life – but can we identify the right approach to render appropriate help when our children need it?

Prof Kutcher, from Dalhousie University and Izaak Walton Killiam Healthcare, was in town recently to speak at the Together Against Stigma (Towards An Inclusive Society) International Conference, sharing his experience to help boost mental health literacy in Singapore.

“We are confusing distress with mental disorder,” he says. As he puts it, being mentally healthy does not equate to feeling good all the time. “Mental health is the capacity to engage with the challenges and opportunities of life, and through that engagement, develop competencies and skills to help one become resilient and deal with them. Sometimes, developing resilience is painful. Like physical health, we have to put in efforts to stay healthy.

“Feeling unhappy, worried or nervous does not mean that you might have an anxiety disorder. It simply means your body is telling you that you have a challenge or opportunity to be addressed.”

He goes on to tackle the thorny issue of those who are overly-invested in shielding children: “It shouldn’t be surprising when students say that they’re worried or stressed about an exam – because it is supposed to be so. The point is, we should teach kids to learn to deal with the trigger signal so it doesn’t worsen or become excessive, and not focus on whether he is or should not be stressed,” Prof Kutcher explains.

“We want to help young people become resilient, but we don’t do this by protecting them from life. We do this by giving them skills to deal with life,” repeats Prof Kutcher. “If we don’t teach (them) the difference between feeling sad and having a depression, when they get sad, they may think they have a depression; when they really have a depression, they may think they’re just having a bad day.”

“With this understanding, people with mental illness can be mentally healthy – if they know how to adapt and practice self-care to help themselves. For example, someone with diabetes can lead a healthy life if they take their medication and pay attention to their diet. In this sense, wellness and (mental) illness are two sides of the same coin,” Prof Kutcher elaborates.

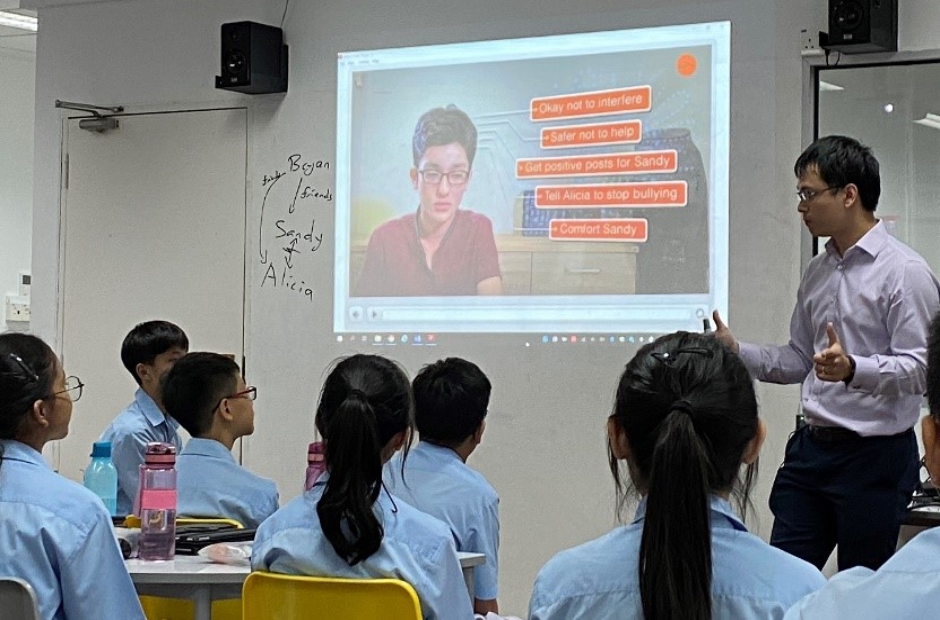

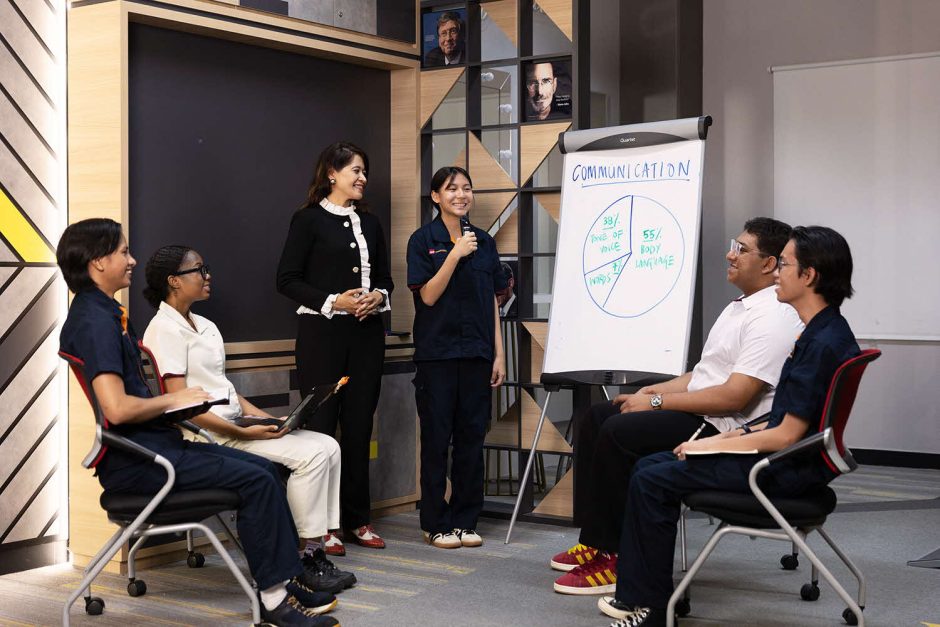

In schools, students learn the importance of mental health, learn coping stategies eg. emotion regulation, relaxation exercises, recognise when they are distressed and seek help. Beyond the skills and strategies, the quality of relationships remain key in helping children build their resilience. Parents and teachers can be a source of support for the children to give them confidence to explore, take risks, sometimes fail, and grow their resilience. As they turn to us for support, we need to encourage help-seeking and journey with them.

For more resources to help our children build resilience for better mental health, check out these links:

For resources related to our children’s mental health, check out these links: