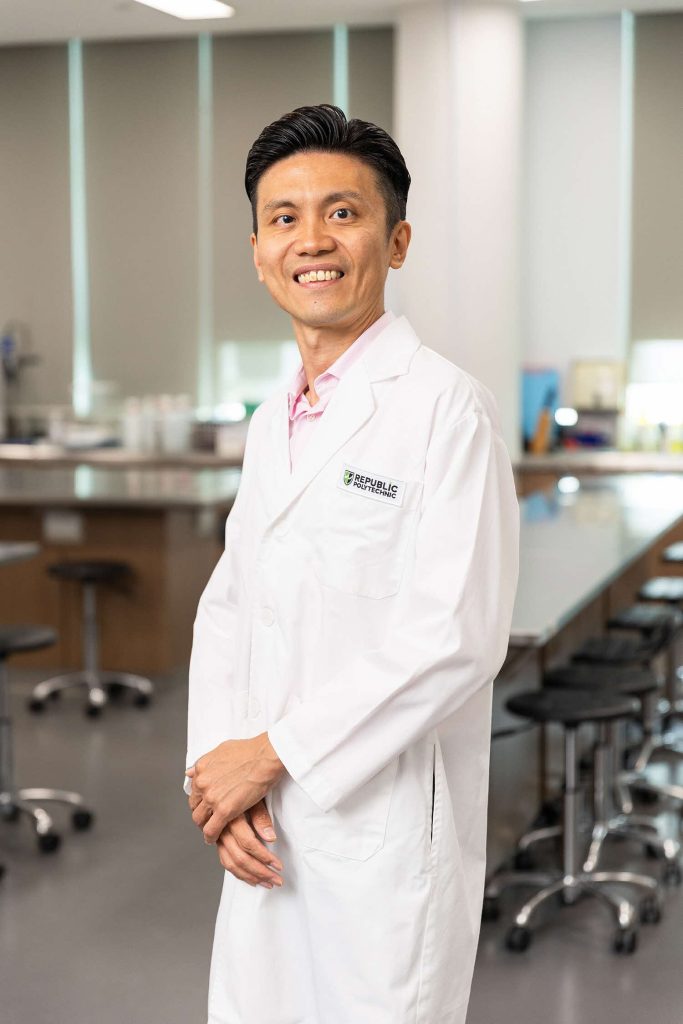

His unapologetically vibrant wardrobe catches the eye – a flash of personality that hints at his teaching style: open, distinctive, and quietly boundary-pushing. It’s more than just flair. It suggests a willingness to stand apart and to create space for others to do the same.

You start to understand that outlook better once you know where Mr Eric Kwek comes from. The Senior Lecturer at Republic Polytechnic’s School of Applied Science didn’t start his career as a teacher. After graduating with a degree in Chemistry, he was unsure of his next steps. He joined Republic Polytechnic as an administrative officer, overseeing timetables and curriculum operations, which also suited his strengths. “I like seeing how everything fits together,” he says. “There’s satisfaction in making sure things run smoothly.”

But what stayed with him weren’t the spreadsheets. It was the fleeting interactions with students: checking in, offering comfort, sensing when someone seemed off.

Born with an eyesight condition that made eye contact and social interaction challenging, he often second-guessed how he was perceived. “I used to avoid eye contact because I was afraid people would think I was being rude,” he shares. That self-consciousness, which had once dented his confidence, also gave him perspective – helping him better understand and support students who struggle in their own ways.

Who, me? A lecturer?

The idea of becoming a lecturer never crossed his mind – until he was invited to teach a Chemistry class, as part of a Republic Polytechnic initiative that gave non-teaching staff the opportunity to try classroom facilitation. The students responded well – but it was his own quiet excitement that surprised him most.

The experience lit a spark – one that made him realise he wanted to teach. Heartened, he embarked on a four-year part-time Master’s in Life Sciences while delicately balancing family and full-time work.

Back then, there was a nationwide push for healthier food choices – a movement that sparked his interest in food science. It became his professional calling, and today he teaches food-science-related modules.

Having never taken the conventional industry route, Mr Kwek understands how wide the gap between theory and practice can feel, and how overwhelming it might be to bridge that gap alone. “I didn’t have that kind of direct industry experience,” he says. “So I had to put myself out there, build connections, ask questions, and learn everything I could for my students’ sake.”

That resolve continues to guide his teaching style. Rather than rely solely on theory, Mr Kwek integrates real regulations and workplace scenarios into his curriculum, drawing from his frequent engagements with industry. This helps students see how industry standards function in context – not just in textbooks.

“People often say, ‘You’ll only understand how this works when you’re in the industry.’ But why wait? Why don’t we bring that experience into the classroom while they are still learning?” he emphasises. “What matters is that students make sense of that world and step into it with confidence.”

Analysing food through different lenses

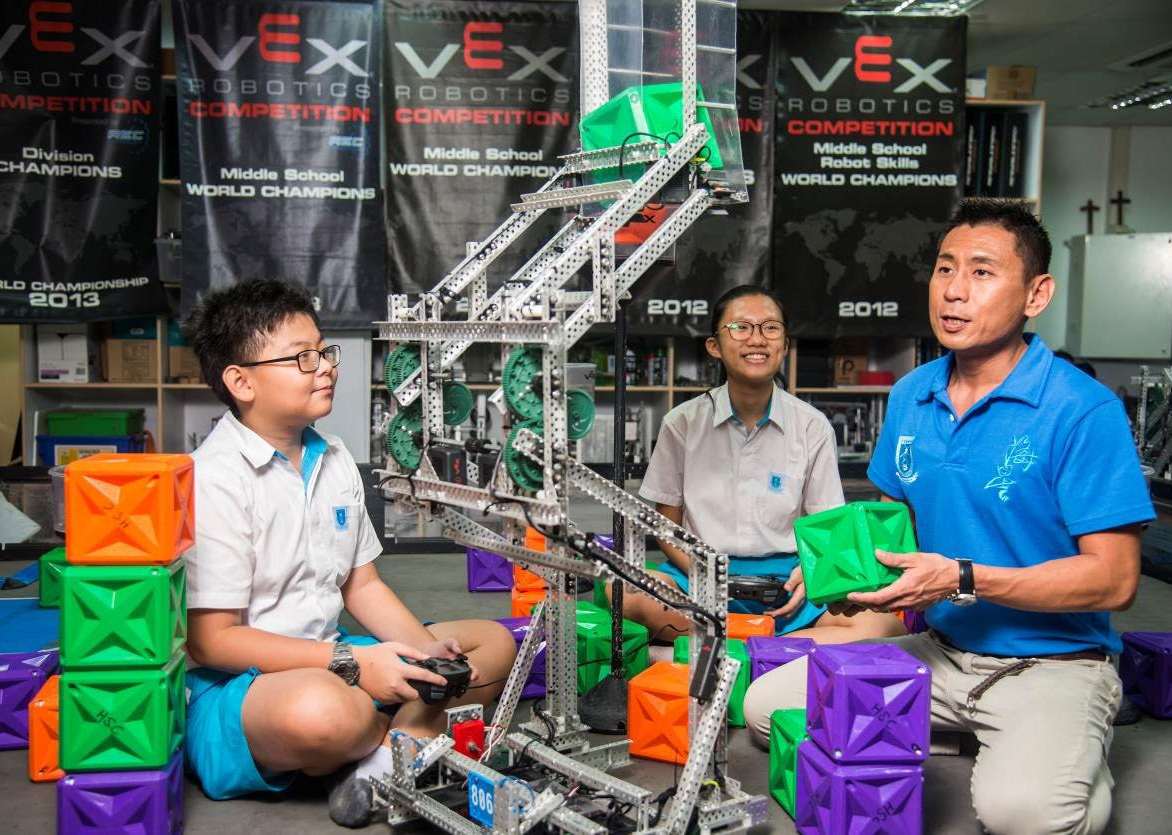

In Mr Kwek’s class, food safety isn’t a dry topic. It’s a dynamic exercise: Students test samples of food deliberately stored under sub-par conditions and analyse the results, mirroring regulatory challenges in compliance with frameworks like the Singapore Food Regulations or HACCP protocols. Such exercises train students to think critically and make informed decisions.

For Mr Kwek, this level of authenticity is deliberate. “I want students to engage with real-life problems, not academic hypotheticals,” he says.

In another collaboration, he worked with colleagues to connect food innovation training with safety protocols. Students first prepared kaya in a food processing and packaging module, focusing on product innovation and presentation. Later, in Mr Kwek’s class, the same group revisited the product – this time through the lens of food safety. They analysed hygiene risks, spoilage timelines, and compliance standards, gaining a multi-faceted view of the food industry.

These hands-on activities drove home a central point. He often encounters this mindset in class: “For a lot of the things that we learn, students will think, ‘Oh, I will just memorise’,” he says. “But in practice, you need to make the judgement calls.”

That same approach guides his work outside of teaching too; Mr Kwek stays involved in the industry to keep his teaching aligned with the evolving realities students will face.

“People often say, ‘You’ll only understand how this works when you’re in the industry.’ But why wait? Why don’t we bring that experience into the classroom while they are still learning?”

Mr Kwek

Embedding training in curriculum

Today, he leads Republic Polytechnic’s team of consultants under the Singapore Food Agency, one of four polytechnics tapped to advise companies on labelling compliance. Mr Kwek also sits on national working groups that review skills training needs and industry engagements to advance food industry practices, bringing those updates to both his students and colleagues.

His professional projects stretch his thinking too, keeping him abreast of food product innovation, safety and regulatory developments so he can support students with confidence.

When he found out students were paying out of pocket to get certifications after graduation, he proposed embedding the training directly into the curriculum. “I thought, why can’t we just do it within the curriculum so that by the time our students graduate, they’re ready,” he explains.

Now, students leave with credentials in hand, confident and industry-prepared from day one.

This impact is only possible through collaboration. Mr Kwek brings in colleagues to co-develop modules and co-run training. He shares what he learns from external projects and supports others’ initiatives, believing that strong partnerships benefit everyone. “If I know I can value-add, I won’t say no,” he says.

Grit behind the grace

That collaborative, student-centred mindset runs through everything he does – whether it is preparing learners with industry-ready skills or offering support when they are overwhelmed.

“You have to pay attention to the small things,” he says. “Sometimes what a student needs most is to be heard and to be believed in.”

A former student, Crystal Tan, now 25, recalls how he noticed she was overwhelmed and offered kind words that made her feel seen and capable. He later nominated her for a competitive internship and entrusted her with a final-year project leadership role, well before she saw her own potential.

“He always made it a point to affirm me in small ways,” she says. “Even when I wasn’t confident in myself, he saw something in me and gave me the chance to prove it.”

“I have a soft spot for students who doubt themselves,” he reflects. “Because I know how that feels.”

He has also stood by his students through mental health struggles. One student, who showed little interest and had difficulty working in groups, was experiencing panic attacks that disrupted lessons. Mr Kwek worked with her and counsellors to make sure she received the assistance she needed, while guiding her classmates to adapt and support her. Over time, she progressed, gaining confidence and doing well in her final year.

“These situations are not easy,” he says. “But you stay calm and offer steady support – even when the student struggles to believe they matter.”