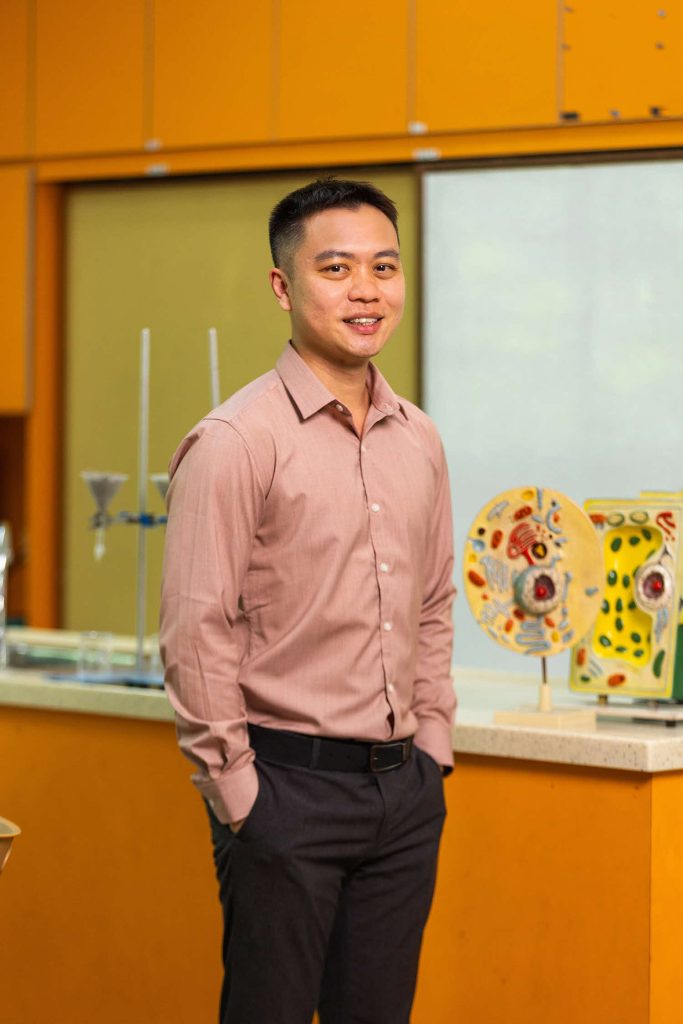

When 12-year-old Adhrit Rayala is asked what plant his teacher would be, he says, “Balsam plant.”

Then, with theatrical flair, he makes an exploding hand gesture to mimic seeds bursting from their pods. Most teachers would be bewildered with the comparison. Mr Jonathan Lo, however, takes it as a compliment, tickled. He even teasingly clarifies with Adhrit if he is referring to the knowledge he imparts, and Adhrit nods emphatically.

It is a metaphor that captures exactly how Mr Lo teaches – knowledge spreading far and wide through his thoughtful pedagogy at Endeavour Primary School.

“He makes science come to life!” Adhrit says, eyes sparkling as he recounts adventures that sound more like treasure hunts than textbook lessons. Like the time Mr Lo mysteriously brought plants to class, only to have students design their own experiments to see how water is transported in plants. Or when a seed collection project sent Adhrit’s family across the island in search of a floating seed found only at West Coast Park.

This is Science education at Endeavour Primary School: experiential, engaging, and transformative.

Rewriting the rules

Where Mr Lo is concerned, “I do not want to teach just based on the textbook. It is boring to learn the flower parts by only reading about them,” he states.

Instead, his lessons unfold like real-world mysteries. And this also applies to Mathematics. To get students to understand percentage change, Mr Lo brought in an example of a movie-ticket promotion that looked great… until students crunched the numbers. What could have been a routine exercise morphed into a masterclass in critical thinking, consumer behaviour, and ethics.

“I asked them about their feelings and opinions about the deal. ‘What do you really think about these promotions? Would you be attracted?’” Soon, the class was debating how companies market to seniors, students, and families, and whether those deals were truly fair.

Then came the twist: Mr Lo told his students that he was misled by the terms of this promotion, and explained how he provided feedback and got a refund. “Even as a teacher, I am still learning.”

That honesty reveals a deeper belief: that good teaching is not just about content, but connection. And it is a conviction forged early in his teaching career.

“I don’t force people to be ready. I wait for them to be ready – because everyone can gain knowledge and grow.”

Mr Lo

Teaching and learning through differentiation

In Mr Lo’s first year of teaching, he found himself supporting a neurodiverse student with behavioural needs. “I had to read up on the condition, try different approaches, and just spend time talking to the student. Not scolding, just talking,” he recalls.

Gradually, the student’s outbursts eased, and he began to settle, learn, and connect.

“It made me a stronger educator,” Mr Lo reflects.

Years later, those lessons continue to serve him. Currently in his third year with a student who has selective mutism, he has developed methods that honour the child’s comfort zone whilst maintaining expectations. He tells the student through written notes and online platforms: “I understand that you may not be comfortable talking, and I am ok with that, but I want to ensure you are learning.”

“I do not force people to be ready,” Mr Lo says. “I wait for them to be ready – because everyone can gain knowledge and grow.”

“Teaching different levels helps me to grow,” he adds. When he adjusts his teaching between one group of students and abilities to another, he does not just adapt the content. Students who are more academically inclined are assigned open-ended challenges; learners who require more guidance receive sentence starters and structured support. “The same objective is achieved, even though the process is differentiated,” he explains.

Digital native, analogue heart

In an era where technology is widely used in education, Mr Lo’s approach is refreshingly purposeful. “I don’t use EdTech for the sake of using it,” he clarifies. “It really depends on the class’ readiness.”

He once showed students how ChatGPT incorrectly solved a complex mathematics pattern question, then issued a challenge to ask ChatGPT three questions to prove that it is wrong. The point was not to trick the tool, but to sharpen students’ thinking. By turning AI into something to question, not copy, Mr Lo made discovery the centre of the lesson – and kept curiosity in the driver’s seat.

Perhaps nothing illustrates Mr Lo’s teaching philosophy better than his Eco Guardians programme. Voluntary and limited to 40 Primary 4 to 6 students, it prioritises commitment over academic results.

“We want to recruit people who really believe in the programme’s mission,” he says about the application process that prioritises genuine commitment over academic achievement.

Being an Eco Guardian is more than just about environmental awareness. Students mentor others through upcycling workshops, present at school assemblies to develop confidence, and manage the hydroponic gardens that supply produce to the Singapore Christian Home.

“The programme is not just about growing vegetables,” he explains. “It’s about nurturing the whole child.”

Fourteen years into his time at Endeavour Primary School, Mr Lo takes setbacks in his stride, adjusting his approach and trying again with optimism. Like the balsam plant his student compared him to, his impact explodes outward, scattering seeds of curiosity, confidence, and care far beyond his classroom.

“That’s what growth is – it doesn’t stop,” he says.