The Primary 6 girl was inconsolable. Tears streamed down her face over her score that was just shy of a better grade.

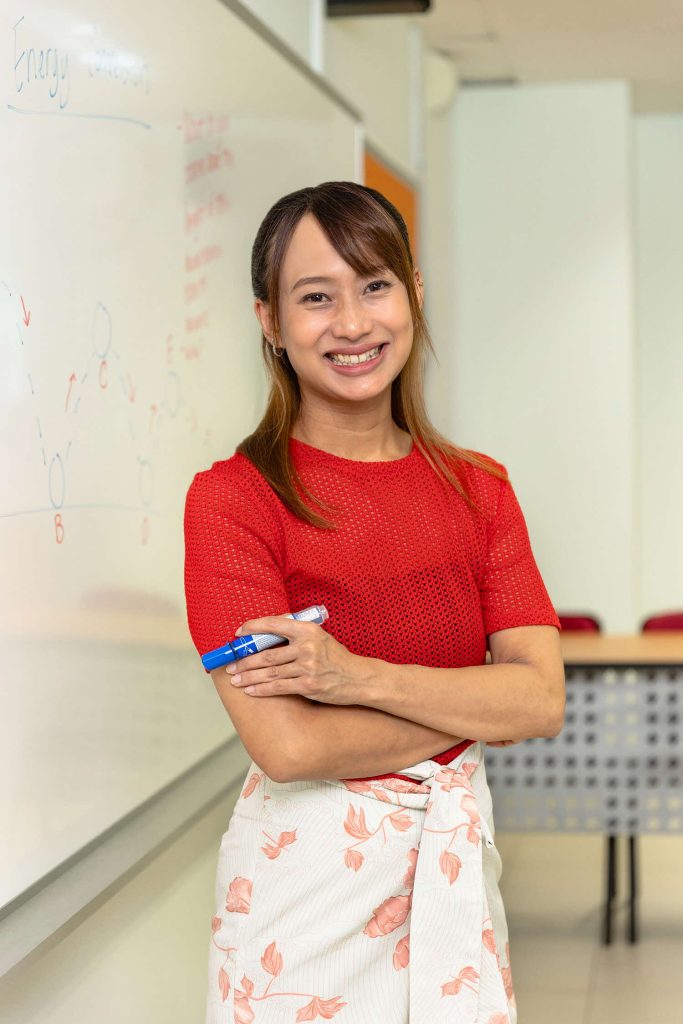

Her teacher Ms Diana Lin, better known to her students as Mrs Tan, was concerned. Here was a child who wanted to become a teacher when she grew up, and loved learning, but was feeling so upset over missing a single percentage point.

While such incidents do not happen frequently, Mrs Tan, who is Kong Hwa School’s School Staff Developer and has been teaching at the school for two decades, says that these incidents crystallise the need to help children see that learning is about growth, not just grades.

Rewriting the rules of mistakes

Mrs Tan, a recipient of the MSEA Gold Award in 2022 and the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan LEAP Award in 2024, has been reshaping how teachers and students across the school approach mistakes.

She worked with her Vice-Principal to create a “Culture of Error”. This approach challenges both teachers and students to see mistakes as learning opportunities rather than something undesirable. The approach required teachers to examine their own reactions to student errors and reflect on how their responses influenced classroom dynamics.

“It took a little bit of time for everyone to get on board,” Mrs Tan acknowledges. “Teachers had to be vulnerable and share how they feel about making mistakes as an adult, and rethink how they react and respond towards their students’ mistakes.”

The conversations were not easy. Teachers admitted to their low tolerance when students repeated the same errors. They struggled with the dilemma of how much encouragement to offer when children kept failing. “Where do you draw the line?” Mrs Tan reflects on those early discussions.

The results are visible in classrooms today. Students willingly attempt difficult problems even when unsure, and try again rather than give up when teachers point out their errors.

“When I put common mistakes on the board without naming who made them, students will openly claim ownership, saying, ‘I wrote that.’ It shows that they are not embarrassed by their errors. In fact, they feel glad that there is a chance for the teacher and the class to talk about them.”

Mrs Tan

“You can see the change in the students,” she says. “During our ‘favourite no’s’ sessions, when I put common mistakes on the board without naming who made them, students will openly claim ownership, saying, ‘I wrote that.’ It shows that they are not embarrassed by their errors. In fact, they feel glad that there is a chance for the teacher and the class to talk about them.”

Soon after the incident of the girl who cried over her “failure”, she stood before her classmates acknowledging her emotions and what she had learned. She recognised she was “too hard on herself” and decided to “set broader goals” and not be too narrow and focus on what she missed out on. That is the power of Mrs Tan’s Culture of Error — normalising mistakes, and humanising success.

Making learning irresistible

It is not just mindsets Mrs Tan aims to change. It is the way students learn too.

Walk into her Science classroom and it buzzes: Students may be solving an escape room puzzle or racing through gamified challenges borrowed from arcade mechanics. “I saw how children love arcade games, so I tried it in my class,” she explains.

On top of games, she uses videos, group projects, and hands-on activities to ensure every student is engaged.

Yet for all her imaginative methods and growth mindset philosophy, nothing would test her teaching abilities – and her own capacity for learning from failure – quite like her encounter with one particular student with special needs.

Two years that trained her patience

Two years ago, a Primary 5 student with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder arrived in Mrs Tan’s class. Even though she was trained to teach students with special needs, she was not quite ready for what lay ahead.

“Sometimes, no matter what I did, the child was still throwing tantrums and having meltdowns.”

The experience pushed Mrs Tan to her limit. Daily phone calls with parents. Constant meltdowns. Moments when she questioned her competence as a teacher. “I doubted myself many times over,” she says.

Eventually, she realised she could not do it alone. “I really had to change my mindset, put aside my ego, and learn to ask for help,” Mrs Tan says. “I called on my Year Head, HOD of Student Management, Special Educational Needs (SEN) officer, and my co-form teacher.”

She also began identifying students who could help their classmate. Six children emerged as constant buddies, who also learned lessons about empathy and inclusion that no textbook could have taught. With those steps and support in place, the student with SEN settled down in the classroom.

“The best people to advocate for children with special needs are the students themselves,” says Mrs Tan of her other learning point. “It was the most challenging two years of my entire teaching life, but it was also the most rewarding. It taught me patience in ways I could have never imagined.”

Leading by stumbling forward

In her leadership role, Mrs Tan now mentors colleagues across the school. When promoting gamification techniques, for example, she videotapes herself teaching, mistakes and all, and uses the footage for professional development sessions.

“In a video, you can also see that during the lesson, there was a student coming back from the toilet and saying the tap did not stop flowing,” she recounts with a laugh.

“It is the reality of teaching, and I made mistakes with this new ICT tool that I was trying out. I told teachers this is part of sharing, exploration, and just go ahead and try.” Her willingness to show vulnerability has built trust among colleagues. “I want to be that positive light for my colleagues, to share whatever works – the good teaching practices,” Mrs Tan says thoughtfully.

What really matters

The joy of teaching centres on two key goals: ensuring children enjoy coming to school and fostering genuine love of learning, says Mrs Tan.

Her empathy for struggling students comes from personal experience: She used to fear public speaking so much, she would stutter. She even planned to pursue a computing career, believing it required the least conversation with others. However, she had a change of heart when she was at university.

“I cannot be hiding in my shell all the time,” she reasoned, and deliberately chose to go into teaching to push herself beyond her comfort zone. Twenty years on, that leap of faith continues to shape lives beyond her own.

“I do not want the students to see learning as a chore, as a paper exercise of just getting to their choice school,” she says. “I want to see that sparkle in their eyes, through the questions that they ask.”

When former students seek her out years later to thank her, Mrs Tan sees the true measure of her success. Academic results may impress, but it is character and resilience that endure.

“Whether the child scored the best marks possible or not, if I know they have done their best, that is good enough for me,” she says. “Every child has got that potential.”

.jpg)